In a future Japan where the joys of childhood are tightly controlled and birth rates have plummeted, the anime series SANDA, adapted from Paru Itagaki’s critically acclaimed manga, plunges viewers into a world where a descendant of Santa Claus holds the key to forgotten wonder and perilous mysteries. As the narrative unfolds, Episode 9, titled “Even Artificial Flowers Can Rot,” delves deeper into the complex psychological landscape of its characters and the dystopian society they inhabit, pushing protagonist Kazushige Sanda further into his reluctant role as Santa.

The Precarious World of SANDA

Set in the year 2080, SANDA‘s Japan is a society obsessed with preserving its dwindling youth. Children are considered national treasures, their lives meticulously managed, including arranged marriages at birth and pervasive surveillance. Traditional holidays like Christmas have been deemed dangerous and have faded into myth, replaced by a “trauma-free” curriculum designed to protect children from hardship. This rigid control, however, has ironically infantilized the youth, stripping them of agency and genuine experience.

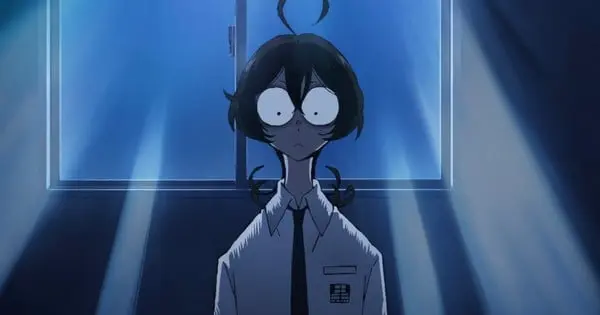

At the center of this world is Kazushige Sanda, an ordinary middle school student who discovers he is a descendant of Santa Claus. His transformation into a hulking, bearded Santa figure, endowed with incredible strength and healing powers, is triggered when his classmate Shiori Fuyumura shatters a mystical seal. Fuyumura, desperate to find her missing friend Ichie Ono, believes Sanda’s powers are essential to her quest and to reignite the lost spirit of Christmas.

Episode 9: “Even Artificial Flowers Can Rot” – Key Developments

Airing on November 28, 2025, SANDA Episode 9, “Even Artificial Flowers Can Rot,” intensifies the series’ exploration of identity, agency, and the cost of an artificially protected existence. The episode builds upon the ongoing conflicts, particularly Sanda’s struggle to embrace his Santa identity while grappling with the ethical dilemmas of his powers, and the increasingly disturbing actions of antagonists who embody the society’s warped ideals.

Sanda’s Training and the Emergence of “Black Santa”

A significant plot point in Episode 9 involves a training arc for Sanda, which leads to the unexpected emergence of his “Black Santa” form. This darker manifestation of Santa is implied to be capable of fighting or “punishing” individuals, even children, a stark contrast to Sanda’s initial reluctance to harm anyone. This development forces Sanda to confront the limitations of his compassionate nature and the harsh realities of his mission to protect children in a world where “bad children” exist. His friend, Amaya, even helps Sanda train to endure being “killed,” highlighting the extreme measures taken in their efforts.

Namatame’s Backstory and Radical Ideology

The episode sheds light on the antagonist Namatame, revealing her disturbing backstory and radical philosophy. Namatame’s belief that “saving people from growing old is a mercy kill” is underscored by a tragic past where she murdered her own mother for cutting off her arm, driven by the desire for eternal youth. This revelation paints Namatame as a sociopath, whose actions are driven by a twisted interpretation of societal pressures regarding aging and rejuvenation, further challenging the “trauma-free” facade of their world.

Ono and Fuyumura’s Complicated Relationship

The relationship between Shiori Fuyumura and Ichie Ono, the catalyst for Sanda’s journey, also reaches a critical juncture. Ono, feeling Fuyumura slipping away, actively tests their relationship. A particularly notable, and somewhat unsettling, scene involves Ono and Fuyumura stripping naked, which Ono herself acknowledges feels “wrong,” despite both characters being 14 years old. This bizarre interaction highlights the distorted perception of age and maturity in their society, where chronological age doesn’t always align with perceived “adulthood.” The episode ends with a cliffhanger as Oshibu confronts Ono, adding another layer of tension to her already precarious situation.

Themes and Broader Implications

“Even Artificial Flowers Can Rot” continues SANDA‘s intricate exploration of societal critique and personal growth. The title itself suggests a decay beneath a polished, artificial surface, mirroring the dystopian world where a fabricated “childhood” conceals deeper issues.

Adolescence and Identity

The episode reinforces SANDA‘s central thesis: that adolescence is inherently awkward and that hardship is necessary for true growth. Sanda’s struggle with his dual identity, and his increasing inability to revert to his normal form without “Bratty Beans,” symbolizes the challenging transition from childhood innocence to adult responsibility. The merging of Sanda and Santa’s inner voices indicates a weakening line between his two identities, suggesting his gradual acceptance and maturation.

The Perils of Excessive Protection

The “Trauma-Free Curriculum” and the society’s hyper-focus on child protection are continuously deconstructed, revealing their detrimental effects. Namatame’s extremist views and Ono’s confused understanding of her own relationships underscore how a society that prioritizes shielding children from all adversity can inadvertently create deeply maladjusted individuals. The episode suggests that authentic experience, even painful ones, are crucial for becoming a well-adjusted adult.

The Unpredictable Narrative of Paru Itagaki

Consistent with Paru Itagaki’s previous work, Beastars, SANDA maintains a chaotic, comedic, and surreal tone. The unpredictable twists, from Sanda’s bizarre transformations to the morally ambiguous actions of its characters, keep viewers engaged. The anime adaptation by Science Saru has been praised for its high-quality animation and ability to capture the unique feel of Itagaki’s original manga, even as it condenses the story’s progression.

As the series approaches its conclusion for the first season (listed with 12 episodes), Episode 9 leaves many loose ends, prompting speculation on how the remaining episodes will attempt to resolve the complex web of plotlines. The fearlessness with which SANDA tackles uncomfortable truths about youth, society, and identity ensures that “Even Artificial Flowers Can Rot” is a thought-provoking installment in this unique and compelling narrative.